Plum Island is a barrier island that shadows the Massachusetts’ shore for roughly nine miles between the mouth of the Merrimack River on the north and the mouth of the Ipswich River on the south. Fires were routinely set on the beach at the northern end of Plum Island to guide mariners into the Merrimack River until 1783, when the Marine Society of Newburyport erected two official day beacons and employed men to display lanterns on them at night.

When these methods proved insufficient, the Massachusetts Assembly gave its approval on November 16, 1787 for the erection of two lighthouses, each with a fixed white light thirty-seven feet above sea level, on the north end of nine-mile long “Plumb Island,” provided the sum “did not exceed £300 lawful money.” When first lit on April 14, 1788, the lights became the thirteenth lighthouse built in America, and were likely America’s first set of range lights. The merchants of Newburyport paid for the construction cost, which came to £266.

A year after navigational aids fell under federal jurisdiction in 1789, President George Washington appointed Abner Lowell as keeper of the Plum Island Range Lights, and it may be that Lowell had been keeping the lights since their inception. Keeper Lowell was a kindly man known by many as “Uncle,” and was the first of three generations of Lowells to man the lights.

In addition to the range lights, a keeper’s dwelling was also built along with a signal house, where flags were raised to alert those on the mainland when a pilot was required or a ship was in distress. At night and during reduced visibility, an alarm gun provided by the Merrimack Humane Society was sounded to call for assistance.

In 1795, Abner received a salary increase from £66 to $266 (about £80) annually, because the light was rather isolated and the soil unfit for tilling.

|

In December 1823, Keeper Lewis Lowell was overcome and died of asphyxiation after inhaling fumes from a charcoal fire he had lit under the lantern to keep the whale oil from congealing. His son Joseph Lowell assumed his duties and remained keeper until 1837, when Captain Phineas George was made keeper. Upon the retirement of Keeper George in 1858, it was noted that he “by his faithful watchings day and night, in the coldest winter blasts, for vessels in distress, and by his superhuman efforts to save life and property in the cold of over twenty winters’ storms, to which his location is subjected, has entirely lost the use of his right arm, and can no longer work.” His wife was described as being “broken in health” by over-exertion in assisting him and raising their eleven children. Frederick D. Carleton replaced Phineas George as keeper.

Congress approved $4,000 in 1838 for “rebuilding” the two lights, but it is likely that the two towers were simply altered and/or repaired as only $950.44 was spent.

Shipwrecks and loss of life were not uncommon in the area. In December 1839 alone, three storms destroyed more than 300 vessels and killed over 150 persons. The wreck of the Richmond Packet on December 22nd, in which the captain’s wife was swept away and drowned, drew considerable attention because the gale blew up so suddenly that the keeper—who had left the light only for a few hours—was unable to return, leaving the lights dark at the harbor’s entrance.

Newburyport was recognized as being of sufficient importance to merit lighthouse towers constructed out of more durable material than wood and to have more powerful lamps, however, the requisite periodic repositioning of the towers precluded this.

In 1842, the two towers were described by Inspector I.W.P. Lewis as “dilapidated, leaky, and out of position to the bar channel.” At that time, the wrought iron lanterns each held eight lamps with 12-inch reflectors. The keeper’s dwelling was also “leaky on all sides” and in need of repair.

Lewis proposed to Stephen Pleasanton, the Treasury auditor responsible for lighthouses, that instead of “the old system of marshalling two crazy old towers about and over the sand hills,” two parallel iron rails should be erected about 108 feet long, and positioned about 100 feet apart. The rails, each holding a lantern with three lamps with 14-inch reflectors, would allow the lights to easily be adjusted in response to the shifting sandbar. For the construction of this novel system, Lewis requested a modest $1,315.91.

Perhaps Pleasanton was influenced by Inspector Lewis’ open criticism of Pleasanton’s friend (and Inspector Lewis’ uncle) Winslow Lewis, whose shoddy building practices resulted in many poorly constructed lighthouses and keepers’ dwellings, as Pleasanton rejected the proposal, choosing instead to repair and refit the towers with new cast-iron lanterns and to move them to better positions.

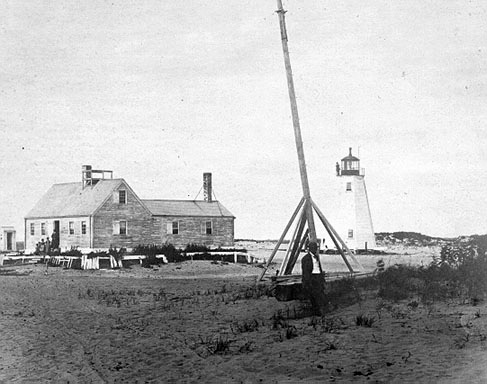

A Bug Light, so-called because it was a smaller, strange-looking tower, was added to the light station in 1855. On August 8th, 1856, the front range tower burned down after being struck by lightning and was not replaced. That same year the rear tower was equipped with a fifth-order Fresnel lens. In 1871, a new fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the fifth-order Fresnel lens. The front light, likely the Bug Light, was described in 1879 as a square structure standing twenty feet high and exhibiting a fixed white light. The tower was situated three hundred feet from the rear tower and was movable.

In 1898, the rear tower, an octagonal wooden tower, was replaced by the current 45-foot wooden conical tower rising fifty feet above sea level. Electricity came to Plum Island Lighthouse in 1927, replacing the kerosene that had been in use since 1877. For a number of years, keepers were assigned the additional duty of maintaining a set of range lights across the mouth of the river at Salisbury Beach after the front light on Plum Island was discontinued.

After the light became automated in 1951, there was no need for a keeper, and the keeper’s dwelling was subsequently used as the headquarters for the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. Friends of Plum Island Light was formed in 1995 to care for the lighthouse. This volunteer group, operating under a lease from the Coast Guard, maintained the lighthouse and occasionally opened it to the public. In 2003, ownership of the lighthouse was transferred from the Coast Guard to the City of Newburyport, which immediately granted a ten-year lease of the tower to the Friends of Plum Island Light.

No comments:

Post a Comment