|

Description: Owls Head Lighthouse, near Rockland Maine, is a place of outstanding beauty, and its history has been replete with remarkable and even mysterious events ever since it was built following President John Quincy Adams' approval in 1824. A couple frozen in ice were brought back to life there, and Spot, a fog-bell-ringing dog, saved his friend from certain disaster. The origin of the name Owls Head is a mystery — whether it came from an imaginative view of a rock formation or from the English translation of the Native American word “Medadacut” will probably never be known.

Owls Head Lighthouse is number one on Coastal Living magazine’s most haunted lighthouse list, and there are said to be at least two ghosts at the lighthouse. One is known as the “Little Lady” and is most frequently found in the kitchen or looking out a window. Doors slam, silverware rattles, but people say her presence brings a feeling of peace. The other is thought to be a keeper from beyond the grave.

A Coast Guard keeper’s wife, Denise Germann said that one night her husband Andy got up to attend to something outside. She rolled over and then felt her husband get back into bed. She asked him a question and upon receiving no reply, turned over to find the bed empty, except for an “indentation of a body” next to her that was moving as if a person was shifting their position. In the morning, Andy told her that when he was going outside, he’d seen “a cloud of smoke hovering over the floor” that passed through him and into the bedroom just before her experience. In the 1980s, two-year-old Claire, (daughter of Gerard and Debbie Graham) woke in the middle of the night to meet her Coast Guardsman father at the top of the stairs and say excitedly, “Fog’s rolling in! Time to put the foghorn on!” Her surprised parents say those terms had never been used in front of her. Over the next two years, Claire described a man with a beard wearing a blue coat and seaman’s cap. “But we knew this was not a real person coming in here,” Debbie said.

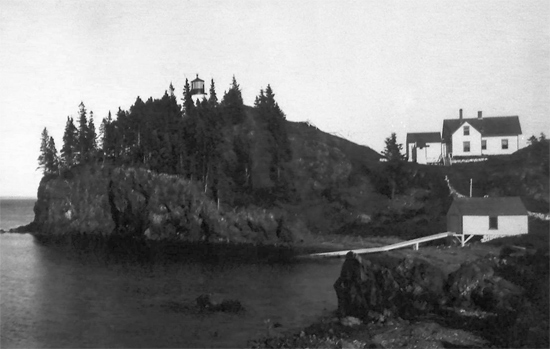

Owls Head Light was built in 1825, for $2707.79 on 17.5 acres of pine covered headland, on the south side of entrance to Rockland Harbor. Even though the conical, rubblestone tower was quite short, only twenty-six-feet-tall, its light could be seen for sixteen miles due to its elevated location.

President John Quincy Adams and Stephen Pleasanton, Fifth Auditor of the Treasury responsible for lighthouses, locked horns over who would be Owls Head’s first keeper. As the position was a political appointment, the President won and the War of 1812 veteran Isaac Stearns (or Sterns) was appointed keeper at an annual salary of $350. Once on her way to trim the wicks, Stearns’ wife Lucy was tossed from the summit and nearly into the sea by a strong gust of wind. Captain Derby of the Revenue Cutter Morris, wrote in 1831 that Owls Head Light was “the most miserable one on the whole coast & I am fearful it will not stand till spring”. He approved of the keeper, writing that the house was neat and “the Keeper & his wife to all appearance [are] excellent people.” Despite repairs, the mortar was no better in 1843. Inspector I.W.P. Lewis wrote that the interior of the tower was covered with ice in the winter and was “in a filthy state.” The tower roof leaked, the lantern had broken panes of glass, and the reflectors were out of alignment. The house was in a comparable state. Keeper Penly Haines confirmed the report, adding, “The distance from the dwelling-house to the tower is 120 feet up a sharp ascent, which, during winter, I find very difficult, and even unsafe in heavy storms.” Despite Lucy Stearns’ accident and Haines’ complaint, it took till 1874 before a set of walkways and stairs linked the dwelling with the light.

Keeper Haines was not given a boat, but was required to travel three miles by land to get supplies. And although he had a good well, it was frequently run dry by ships landing to replace their own water supplies. Seven years on, in 1850, an inspection noted the same conditions. “One of the most terrible storms we have ever witnessed,” wrote the Lime Rock Gazette, hit Rockland on December 22, 1850. A small schooner set anchor in the harbor early in the storm, and its captain went ashore leaving the mate Richard B. Ingraham, a crewman Roger Elliot, and a passenger Lydia Dyer—Ingraham’s fiancée. As the storm intensified, the schooner was torn from its mooring and dashed onto the rocks near Owls Head Light. Its three occupants huddled close together and pulled blankets around them for warmth and protection. As the schooner was breaking up, Elliot sought help by going to shore. The keeper, who was out driving his sleigh, spied Elliott and took him to the lighthouse to revive him. Nearly unable to speak, Elliot pled for help to be sent for Dyer and Ingraham. A search party was organized, and the two were discovered encased in a block of ice formed from the spray. Although the couple appeared dead, the rescuers refused to give up. They chipped off the ice and put the man and woman in cold water. Bit by bit, they increased the temperature and massaged and exercised the pair’s limbs. After nearly two hours, Dyer showed signs of life. An hour later, Ingraham opened his eyes and asked, “What is all this? Where are we?” It took months for the couple to regain their health, but Elliot never fully did. Dyer and Ingraham went on to marry and raise four children. In 1852, a round, twenty-four-foot-tall tower, built of “the best hard burnt brick” replaced the original dilapidated stone tower. Finally, in 1854, a new one-and-a-half-story, wood-frame keepers dwelling was built. A fourth-order Fresnel lens took the place of the eight-oil-lamp apparatus with fifteen-inch reflectors in 1856. In 1869, a small fog bell was attached to the porch of the tower. Then in 1879, a fog bell operated by a Stevens striking machine was installed in a wooden, pyramidal tower. The keeper needed to turn a large crank to set the clockwork mechanism in action. When visibility was low, the bell rang every seven seconds and nearly deafened anyone nearby. The house received a pump and piping for water in 1880, and in 1894 an oil house was erected. In 1898, “a boundary fence was built to enclose the whole reservation”, and a telephone line connecting the station with Owls Head Village was paid for with an appropriation for national defense. In 1903, a covered way, about sixty feet long, was placed over the stairs linking the oil house and lighthouse, and three years later, the covering was extended about 100 feet to reach the dwelling. The covered way was removed in the 1920s. A famous lifesaving resident of the station was Spot, a springer spaniel owned by Augustus (Gus) B. Hamor (keeper 1930—1941). Gus’ daughters Pauline and Millie taught Spot to pull on the rope to ring the fog bell. Whenever a vessel passed by, Spot would ring the bell and receive the sound of a bell or horn from the ship in return. As Spot’s favorite visitor was the mail boat skippered by Stuart Ames, who always brought a special treat for him, Spot came to recognize the sound of the boat’s engine. Once when a terrible snow storm blew in, the snow banks muffled the sound of the bell. Mrs. Ames worried that her husband was lost in the blizzard, but during the thick of the storm, Spot scratched to be let out and raced to the shore, where he barked loudly and incessantly. Then the sound of the mail boat whistle was heard in reply. Stuart had heard the barking and calculated his position, which saved him from crashing into the promontory. Owls Head was automated in 1989, but Coast Guard personnel continue to use the keeper’s dwelling as a residence. In 2007, the Coast Guard leased the tower to the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF), which has proved to be a more than able caretaker. During the summer of 2010, ALF saw to an extensive, but sensitive renovation of the tower. Thanks to $80,000 from the ALF and $168,000 from the Coast Guard, the rust and peeling paint has been banished, and the tower has been restored to its original 1852 appearance. The bricks were repointed and repaired before being repainted. The lantern’s ironwork was restored and its windowpanes replaced, and the parapet’s floor was repaired, in addition to replacing the iron railing and granite gallery supporting the lantern. After the light’s renovation, the ghostly keeper must feel right at home. In 2012, the American Lighthouse Foundation announced that it had licensed the keeper's dwelling at Owls Head from the Coast Guard and would be opening it late that year as an educational interpretive center. The former residence will also serve as headquarters for the organization, which cares for more than twenty lighthouses throughout New England. |

Thursday, March 6, 2014

Owl's Head Light Maine

Got top this one on the 2012 trip - Beautiful location, kind of hard to get to as I remember

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment