For many years preceding the birth of our nation, pirates were far more appreciative of the importance of Cape Henry than was the Virginia House of Burgesses. With the cape lacking a proper light, beacon fires were used as a makeshift navigational aid, and unscrupulous men would capture those in charge of the fires and move the light southward to lure ships aground. As the wreckage continued to mount, men like Virginia Governor Alexander Spotswood petitioned the Assembly to take action. In 1720 this body resolved to construct the light, “Provided the Province of Maryland will contribute...”

Receiving little but passive cooperation from their neighbors, the Virginia Assembly was further hampered by the reluctance of the British Board of Trade to grants its permission to proceed. Since the lighthouse was to be financed in part by shipping duties, the consent of this august body was required. Governor Spotswood argued a strong case, describing the plight of merchants too frightened to venture into the Chesapeake during foul weather. He reasoned: “If such a lighthouse were built ships might then boldly venture, there being water enough and a good channell within little more than a musquett shote of the place where this lighthouse may be placed.” Yet it was only in 1758, and at the behest of concerned tobacco merchants, that the Board threw their weight behind the project.

|

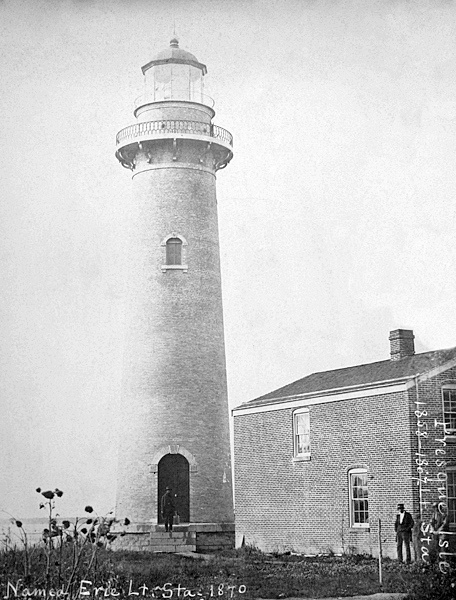

In many respects, Old Cape Henry lighthouse is inextricably linked with the birth of our nation. The Aquia sandstone for its base was gathered from the same Virginia quarries that provided material for Mount Vernon, the U.S. Capitol Building, and the White House. At the first session of the first Congress in 1789, an act was passed which placed the lighthouse service under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Treasury. Included in this act was the provision for the construction of Cape Henry Lighthouse, giving it the distinction of being the first lighthouse ordered and financed by the federal government. The Virginia Assembly, mindful of its own difficulties in building the lighthouse, moved rapidly and ceded two acres in the County of Princess Anne to the United States. President Washington himself took an interest in the construction, noting in a 1790 diary entry that he had spoken with Alexander Hamilton (the Secretary of the Treasury), “respecting the appointment of Superintendents of the Light House, Buoys, etc, and for building one at Cape Henry.”

Secretary Hamilton contracted with a New York bricklayer named John McComb, Jr. to undertake the project at a cost of $15,200. The contract called for McComb, with “all convenient speed, (to) build and finish in a good workman like manner a Light House of Stone, Faced with hewn or hammer dressed Stone...from the bottom of the Water Table up to the top of the Stone Work.” The contract also specified a two-story frame house of twenty feet square, for the keeper, as well as a buried vault for the storage of lamp oil.

The construction proved to be a difficult task, though Hamilton’s representative on the scene describes a highly motivated and uncomplaining John McComb: “He is persevering and merits much for his industry, the drifting of the sand is truly vexatious, for in an instant there came down fifty cart loads at least, in the foundation after it was cleaned for laying the stone, which he bore with great patience and immediately set to work and removed it without a murmur as to the payment for the additional work...” The builder did have to be compensated an additional $2,500, however, as the foundation had to be laid at a depth of twenty feet rather than the planned thirteen, owing to the sandy condition of the ground. McComb estimated that he would finish the lighthouse by October 1792, and this is indeed when it was first lighted.

Lemuel Cornick, who had overseen the construction of the lighthouse, applied to be its first keeper, but President George Washington awarded this honor to William Lewis, who had been one of his loyal troops during the Revolutionary War. Keeper Lewis died just a month after his appointment, and Lemuel Cornick got his chance to run the light. Though he had desired the position, Cornick abandoned the job less than a year later, and Laban Goffigan was made the light’s third keeper.

|

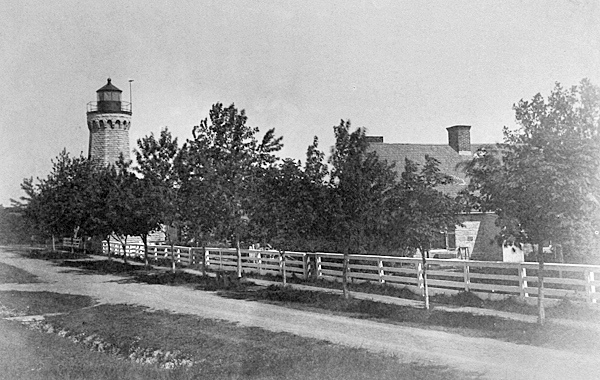

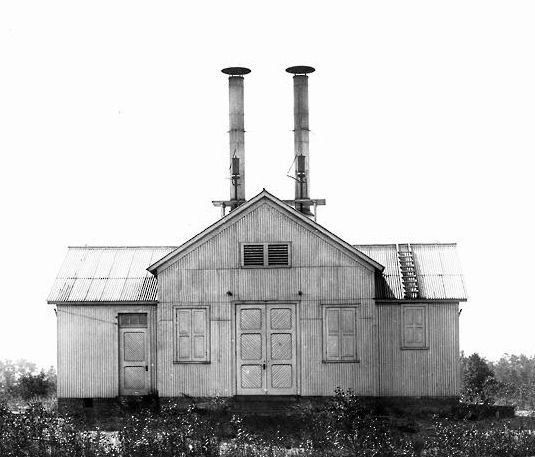

Like most of its comrades, the light at Cape Henry underwent numerous repairs and technological upgrades in the ensuing years. In 1835, a new house was built for the keeper, and in 1841, the lantern was completely redone by Winslow Lewis with eighteen new lamps with brass burners and eighteen reflectors. This work was performed at a cost of $4,000 and included replacement of the wooden deck near the summit with a soapstone deck laid over a brick arch. In 1844, a fifteen-foot-high wall was built around the tower’s base and that area was paved over. In 1855, a fog bell tower was added, and in 1857, the tower was lined with brick and a second-order Fresnel lens replaced the array of lamps and reflectors. Other innovations included the types of oil used in the lantern; these varied from whale oil to cabbage, lard, and kerosene oil, which was adopted near the turn of the century.

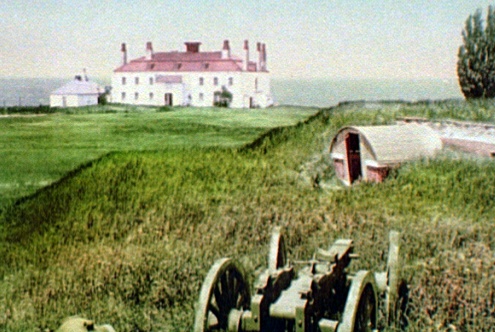

The Civil War temporarily put Cape Henry out of commission. In April 1861, men from Princes Anne County seized the tower and destroyed the lamps and lens. It is likely that the Confederate states (including Virginia) feared the formidable sea power of the Union and sought to make it difficult for them to enter the vital Chesapeake. A lightship was anchored off the cape to serve Union forces until 1863, when Cape Henry Lighthouse was repaired, put back in operation, and placed under military guard.

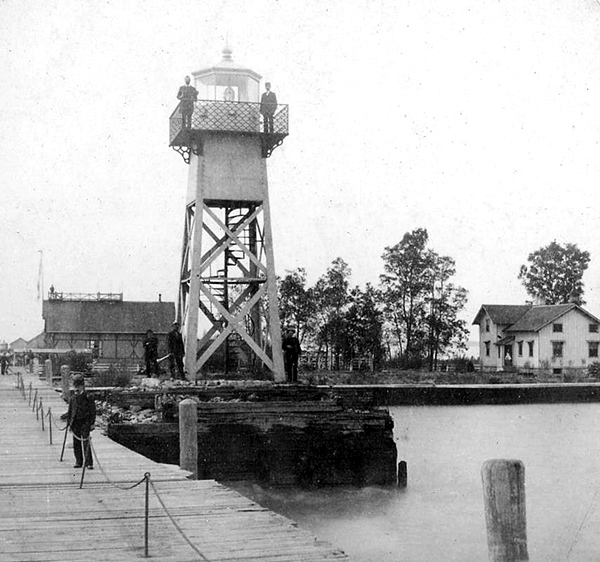

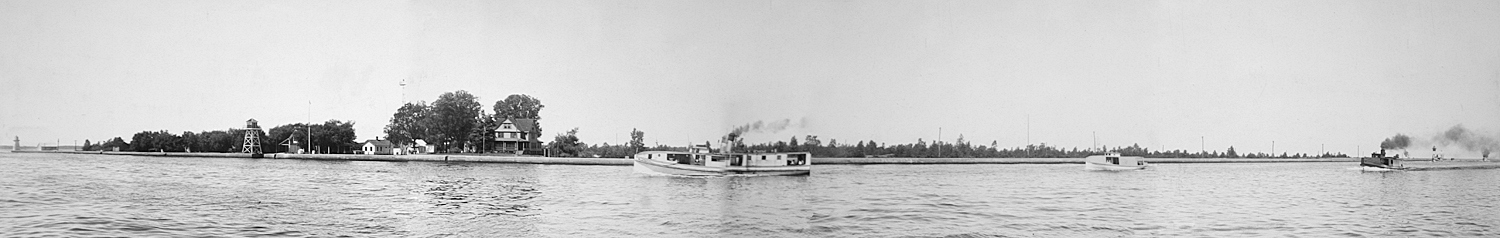

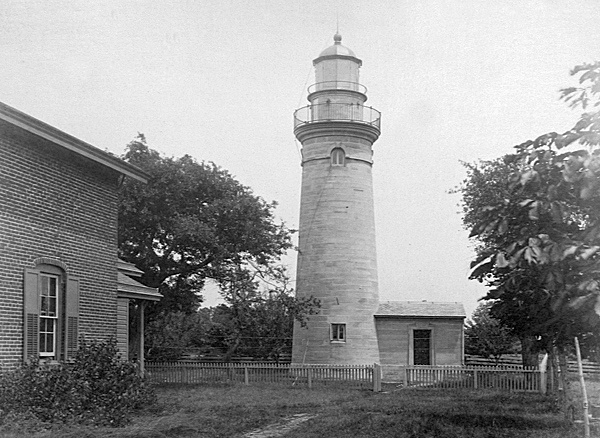

In 1864, an inspector finally corroborated Latrobe’s observation, remarking that Cape Henry was endangered by its oil soaked wooden staircase, which was at this point “greatly decayed and insecure.” The inspector recommended a cast-iron spiral staircase, and this was subsequently installed. The tower remained strong for eight more years, but in 1872 the district engineer noticed large cracks “extending from the base upward” on six of the eight masonry walls comprising the octagonal structure. The inspector concluded that some of these cracks were inconsequential, but those on the north and south faces were compounded by the presence of windows. The inspector concluded that the tower was unsafe and “in danger of being thrown down by some heavy gale.” The construction of a new first-order lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling was recommended, but it took six years for the necessary $75,000 to be appropriated. In 1881, Keeper Jay Edwards transferred his attentions to the new cast-iron structure. Standing 350 feet southeast from the old tower, it was first lighted on December 15, 1881.

Somewhat surprisingly, Old Cape Henry lighthouse has neither crumbled nor been swept away in a storm. Today it stands in silent idleness, next to and somewhat higher than its replacement, owing to its location on the summit of the dune. It remains an indelible landmark, and in 1896 was graced with the presence of the members of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA). They placed upon the old light a plaque commemorating it as the site of the first landing in 1607 of English colonists on Virginia soil. It thereby became the predecessor of the Cape Henry Memorial, to which its shadow reaches on a late summer afternoon. On June 18, 1930, the U.S. Congress ceded the light and land to the APVA, to be preserved in perpetuity as an historic landmark.

In 1939, Old Cape Henry Lighthouse was selected as the site to celebrate 150 years of the Lighthouse Service, and it was this same year that lighthouse maintenance was transferred from the Treasury Department to the Coast Guard. Today, the lighthouse grounds are encompassed by Fort Story Military Reservation and are a noteworthy destination for visitors to the nearby Colonial National Historic Park. Old Cape Henry is the fourth oldest lighthouse still standing in the United States. The lighthouse was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 2002.