Was able to get to two lighthouses today-

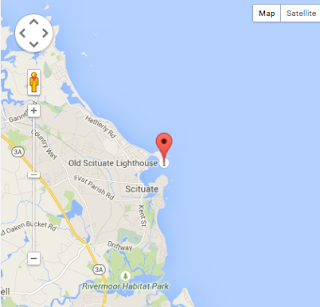

First was the Minot Ledge Lighthouse, just off the coast near Scituate, Mass.

There were a couple of markers at the site as well. The light is actually two miles off the coast, but there is a park that holds a replica light tower and the forms used to build the light.

|

| The forms used to build the light |

|

| The park view |

With its grey stone tower rising almost magically out of the water and its distinctive 1-4-3 flash cycle that has caused romantics to dub it the “I-Love-You” light, Minot’s Ledge is often called one of the most romantic lighthouses in the country. Situated two and a half miles from the shore, the lighthouse is visible for miles but accessible only by boat. Since its beginning over a hundred and fifty years ago, Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse has inspired awe in a broad spectrum of visitors ranging from the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Helen Keller.

However, the light’s base, an almost invisible outcropping of rocks off Cohasset, MA, has plagued mariners for more years than the light has protected them. As early as 1695, a schooner crashed on those treacherous rocks and sank, leaving no survivors. Even before the White Man saw his ships wrecked in those waters, Indians had lived in awe of the evil spirit “Hobomock” who dwelt beneath the rocks and unleashed violent storms. During low tide when the sea was calm, the Indians would paddle out to offer dishes, ornaments, and beads as sacrifices to appease the “Wicked One.” Apparently these offerings were rejected, since by the 1750’s eighty ships and 400 lives had been lost in the surrounding waters. The tragedy that earned the area its name happened in 1754, when a prominent Boston merchant named George Minot lost a valuable ship there; henceforth it was called Minot’s Ledge.

The need for a beacon at the ledge was not lost on lighthouse inspector I. W. P. Lewis, who submitted a report in 1843 detailing the more than forty vessels that had met their end in the previous decade as a result of the ledge. He asserted that the area was “annually the scene of the most heart-rending disasters.” The Lighthouse Establishment heard and responded. Captain William H. Swift, an engineer in the U.S. Topographical Department, feared it would be impossible to build a traditional solid cylinder that could survive full exposure to the ocean. Instead, Swift proposed a radical new design consisting of nine iron pilings cemented five feet into the submerged rock, atop which would perch the lantern and keeper’s dwelling. The reasoning was that the legs would offer almost no resistance to the wind and water. In 1847 a crew began working from a schooner anchored next to the ledge, and over two years and $39,000 later, on January 1, 1850, Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse was illuminated for the first time.

Henry David Thoreau described passing Minot’s Ledge Light in 1849: “Here was the new iron light-house, then unfinished, in the shape of an egg-shell painted red, and placed high on iron pillars, like the ovum of a sea monster floating on the waves…When I passed it the next summer it was finished and two men lived in it, and a lighthouse keeper said that in a recent gale it had rocked so as to shake the plates off the table. Think of making your bed thus in the crest of a breaker!”

Indeed life inside the lighthouse did prove precarious. The keeper’s pet cat was the first casualty of the tower, which swayed so dramatically during a storm that the panicked animal jumped to its death. Only three months into his tenure as keeper, sitting in the living quarters halfway up the tower and supposedly out of reach of the waves, Isaac Dunham wrote “The wind E. blowing very hard with an ugly sea which makes the light reel like a Drunken Man—I hope God will in mercy still the raging sea—or we must perish…God only knows what the end will be.” By October of 1850, Dunham quit, and John Bennett took his place, only to despair soon afterwards at his perilous situation in storms. On April 16, 1851, the fierce winds of a nor’easter left the tower reeling in the pounding seas and blinding snow. During a brief lull at the outset of the storm, Keeper Bennett had rowed across to Boston and disappeared, but his two assistant keepers, Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine, were in the tower fearing for their lives. Wilson climbed up the iron ladder to light the lantern, but found it impossible to descend to the living quarters. Some time around 1am residents on the mainland could hear the keepers furiously ringing the fog bell. As the iron supports began to snap one by one, the bell was silenced, the beacon was extinguished, and the men were cast into the raging sea. The first light of dawn revealed only the bent remains of a few pilings. Two days later a Gloucester fisherman found a bottle containing a final message from the doomed keepers: “The beacon cannot last any longer. She is shaking a good three feet each way as I write. God bless you all.” The body of Joseph Antoine washed ashore later at Nantasket. Joseph Wilson managed to reach Gull Rock, probably mistaking it for the mainland, where he apparently died of exhaustion and exposure.

The sad fate of the first light did not spell defeat for mariners seeking guidance. A lightship was stationed near Minot’s Ledge from 1851 to 1860, and in 1855 construction began on a new stone tower that would be called the greatest achievement in American lighthouse engineering. Supervising the building was Captain Barton S. Alexander of the U.S. Topographical Engineers.

Construction wasn’t easy. In this design, interlocking granite blocks were placed on foundation stones weighing two tons each. The granite had to be cut and assembled on an island attached to the mainland and then dragged by oxen to a vessel that would transport the stone out to the ledge. Of course placement of the granite blocks was conducted only at low tide when the sea was calm; even so, many times construction workers were swept off the rocks by the waves. To prevent further casualties, the aptly named Captain Michael Neptune Brennock was hired as a lifeguard, and only workers who could swim were employed. These were good precautions, but unfortunately they couldn’t avert all danger. Two years into the construction a ship named The New Empire wrecked on the rocks and destroyed what had been built of the lighthouse. Undaunted, Captain Alexander began anew, and after three more years, six thousand tons of granite supported a bronze lantern nearly 100 feet in the air. On August 22, 1860, the second-order Fresnel lens was lit and Minot’s Ledge was once again illuminated. At $300,000, it was one of the most expensive lighthouses in American history. The money was well spent, though; although many waves have crashed over the 97-foot tower and even broken windows, the light has sustained no structural damage.

Life for the keepers of Minot’s Ledge Light remained difficult, though not fatal. Waves have actually crashed over the top of the lighthouse during severe storms, and its inaccessibility, especially during inclement weather, made the delivery of supplies difficult and visiting the mainland sometimes impossible. The solitude and thunderous crashing of the waves drove more than one keeper insane.

The tower’s second-order Fresnel lens was damaged by vandals and replaced with a third-order lens in 1964. The new lens remained atop the tower until 1971, when it an automated solar-powered light was installed. The third-order lens is now found on Government Island inside a replica of the lantern room that sits atop some of the granite blocks that were removed in 1987 during a renovation of the lighthouse. The station’s fog bell survived an unsuccessful robbery attempt and is also on display by the lantern room. The keeper's dwelling at Government Island, which housed the Minot’s Ledge keepers when on shore leave, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The structure underwent a $200,000 restoration in 1992-93, and the ground floor has a hall used for community events. Also found on Government Island is a monument, dedicated in 2000, honoring the two assistant keepers who perished in the original Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse. Construction ringsused for cutting and assembling the granite blocks used in the tower can also be seen on the island.

Although the area is no longer populated by Indians who believe in the evil spirit of “Hobomock”, for years tales have abounded of strange moaning, tapping, and even mysterious polishing of the glass lenses by ghostly hands. A crew of Portuguese fishermen swore they saw a figure hanging on to an outer ladder shouting at them in their own language to keep away, and many local fishermen have reported hearing moans and cries for help coming from the base of the lighthouse. Several keepers were convinced that the ghost of the two doomed assistant keepers still resided in the lighthouse, sending signals to each other, cleaning the lens, and warning others of the dangers presented by Minot’s Ledge. Perhaps it’s best that the lighthouse has been left for the ghosts to inhabit in solitude.

In June of 2007, Coast Guard Maritime Safety and Security Team divers were transported to the waters near Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Abbie Burgess. Their mission was to explore the seabed for the remains of the first Minot's Ledge Lighthouse that collapsed in 1851. On the third day of the expedition, remnants of iron beams, believed to be support legs for the fallen lighthouse, were located with the assistance of a remote operated vehicle. At the conclusion of the operation, a memorial plaque honoring Joseph Antoine and Joseph Wilson, the two keepers lost with the lighthouse, was lowered to the seafloor.

A Notice of Availability, date June 30, 2009, announced that Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, deemed excess by the Coast Guard, was being offered at no cost to eligible entities, including federal, state, and local agencies, non-profit corporations, and educational organizations under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. Interested parties had sixty days to submit a letter of interest, after which they would be given an opportunity to inspect the lighthouse.

When no interested party was found to assume ownership, Minot's Ledge Lighthouse was placed on the auction block on June 25, 2014. The auction attracted seven bidders, who submitted a total of seventy bids, and ended on October 13, 2014, with a high bid of $222,000. The identity of the new owner was soon revealed to be Bobby Sager, a Boston philanthropist and Polaroid chairman.

There are 2 Markers at the light, one for the light itself, and one that honors the original lightkeepers:

On this site 3,514 tons of Quincy granite were hewn into 1,079 dovetailed blocks whose final weight totalled 2,367 tons. On the two circular forms seen here, the cut stones were carefully assembled to assure perfect fit; then disassembled and transported to Minot’s Ledge where they were erected to form the 114 foot Lighthouse which still stands.

Restored by the Cohasset Historical Society

1967

Also, this one:

And for the keepers:

Dedicated to the memory of Joseph Antoine and Joseph Wilson, keepers of the first Minot Ledge Lighthouse who, while manning the Light on the night of Apr. 17, 1851, lost their lives when the lighthouse was swept into the sea during a violent northeast storm.

“They kept a good light.”

Then its was over to the town of Scituate, for the beautiful Scituate Lighthouse:

Although it is the fifth oldest light in New England and the eleventh oldest in the United States, Scituate Lighthouse, on the South Shore of Boston, Massachusetts, is far more famous for the actions of two quick-thinking girls The Army of Two. These heroines of the War of 1812 lived at Scituate Lighthouse and have been immortalized in a number of books and publications.

While Scituates small, protected harbor encouraged the growth of a notable fishing community, mudflats and shallow water made entering the harbor tricky. In 1807, the towns selectmen were petitioned by Jesse Dunbar, a shipmaster, and other residents to construct a lighthouse, and in 1810, Congress appropriated $4,000 for the task.

Unlike sites where the land was purchased, the plot on Cedar Point was seized under eminent domain. Its disgruntled owner Benjamin Baker later denied access through his land and feuded with the first keeper.

Three men from nearby Hingman Nathaniel Gill, Charles Gill, and Joseph Hammond Jr.built the 1 story house, the twenty-five-foot octagonal, split granite block tower, a 12x18-foot oil vault, and a well for $3,200. The trio managed to finish the work in September 1811, two months ahead of schedule. Captain Simeon Bates was appointed first keeper that December. Bates, his wife Rachel, and nine children lived at the light, where he remained until his death in 1834 at ninety-nine years of age.

There is a National Register Plaque on the lighthouse as well.

There was supposed to be a stamp at the Scituate Historical Society, but they didn't know about it.

There is a marker for the Italian Freighter Etrusco which sank at the light in 1956-

The Italian freighter Etrusco, a 7000 ton liberty ship, grounded here March 16, 1956, in a northeast blizzard. All hands safe. Refloated November 22, 1956.

Placed by the Cedar Point Association on the 30th anniversary of grounding and the 350th year of Scituate's incorporation.